My name is Asya Ilgün. I’m a designer and researcher working across disciplines and communities to imagine and build new ways of living with other species.

I recently completed a PhD in architecture at the Institute of Architecture and Media at the Technical University of Graz, where I explored how digital tools and living materials—like fungi—can come together to shape structures that support both humans and other forms of life. My main project during this time was creating a beehive made from mycelium as part of the EU-funded HIVEOPOLIS project at the Artificial Life Lab of the Institute of Biology, Uni Graz. There I collaborated with biologists and ethologists to better understand how insects like honeybees behave and live, as well as designing experiments for biological evaluation. I contributed to research that blended design, biology, and technology—looking at everything from how hives are shaped to how we might grow future building materials from natural organisms. You can check the article I wrote for Driving Design II, edited by Distributed Design, where I explain and share the processes and concepts of this beehive.

Before that, I studied at the Royal Danish Academy’s CITA Studio, focusing on material design and computational methods that can help reimagine architecture as something more inclusive of under explored comfort standards for humans and non-human life. This was the first time I used a WASP3D machine, as we had an industrial 4070 plastic printer at the academy and my thesis prototype was featured in an article. As a result of this project and its impact, I became a member of Distributed Design Platform in 2017.

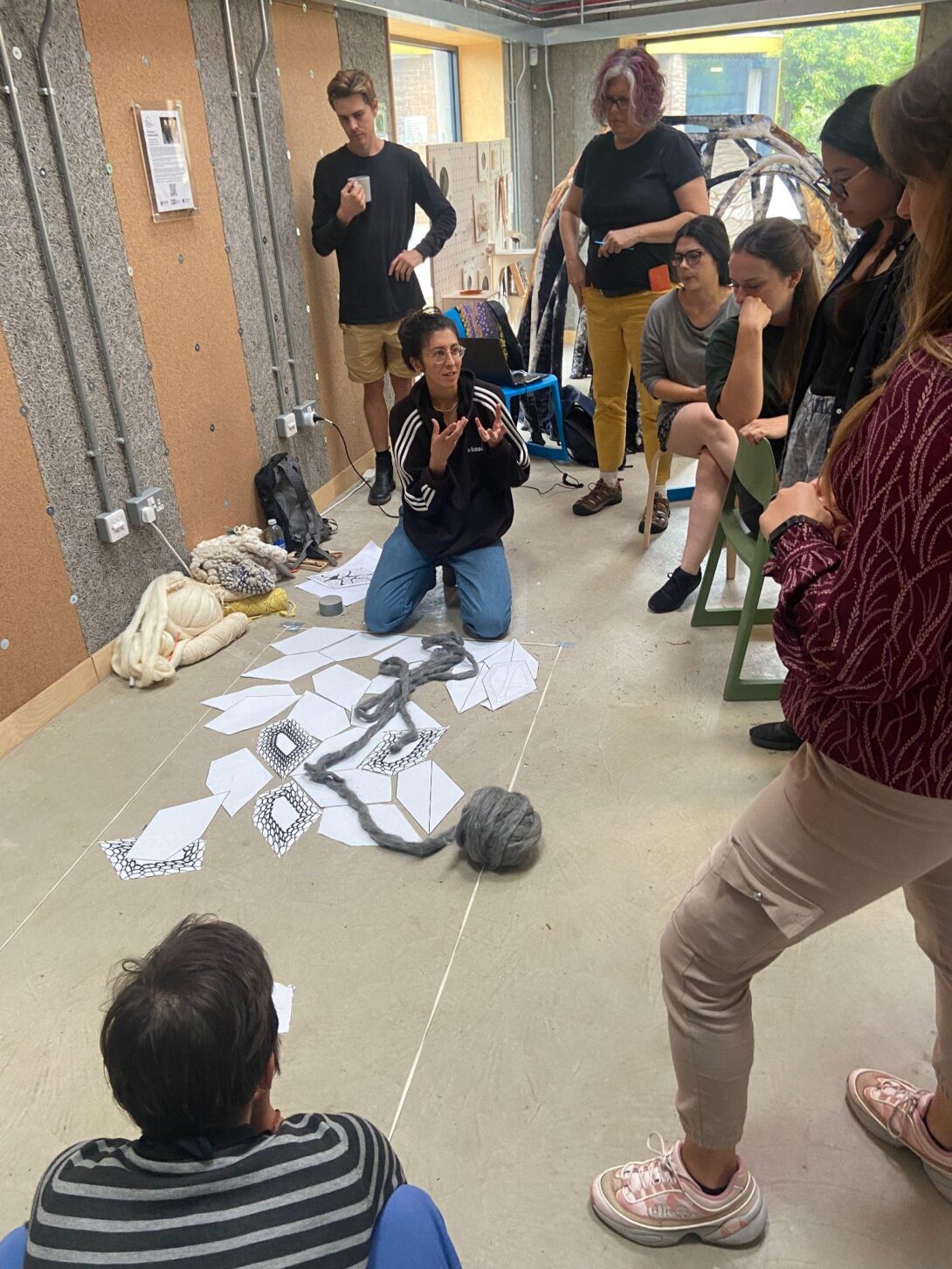

A significant community project which expanded my ways of working and living is the I.N.S.E.C.T. Summercamp and its associated collective that I co-founded in 2022, a hands-on, co-creative platform now in its fourth year. It brings together people from different backgrounds to explore how we might create shared habitats, stories and futures with insects and other overlooked life forms. Since the beginning of this year, I have been part of a research project called WeB: Weaving as Worlding Practice with Earthbeings, through which we are going to bridge I.N.S.E.C.T. Collective and people of Sarayaku, a Kichwa indigenous community based in Ecuadorian Amazons. My focus is slowly shifting from technological solutionism to a more holistic approach to attending to the issues we are facing.

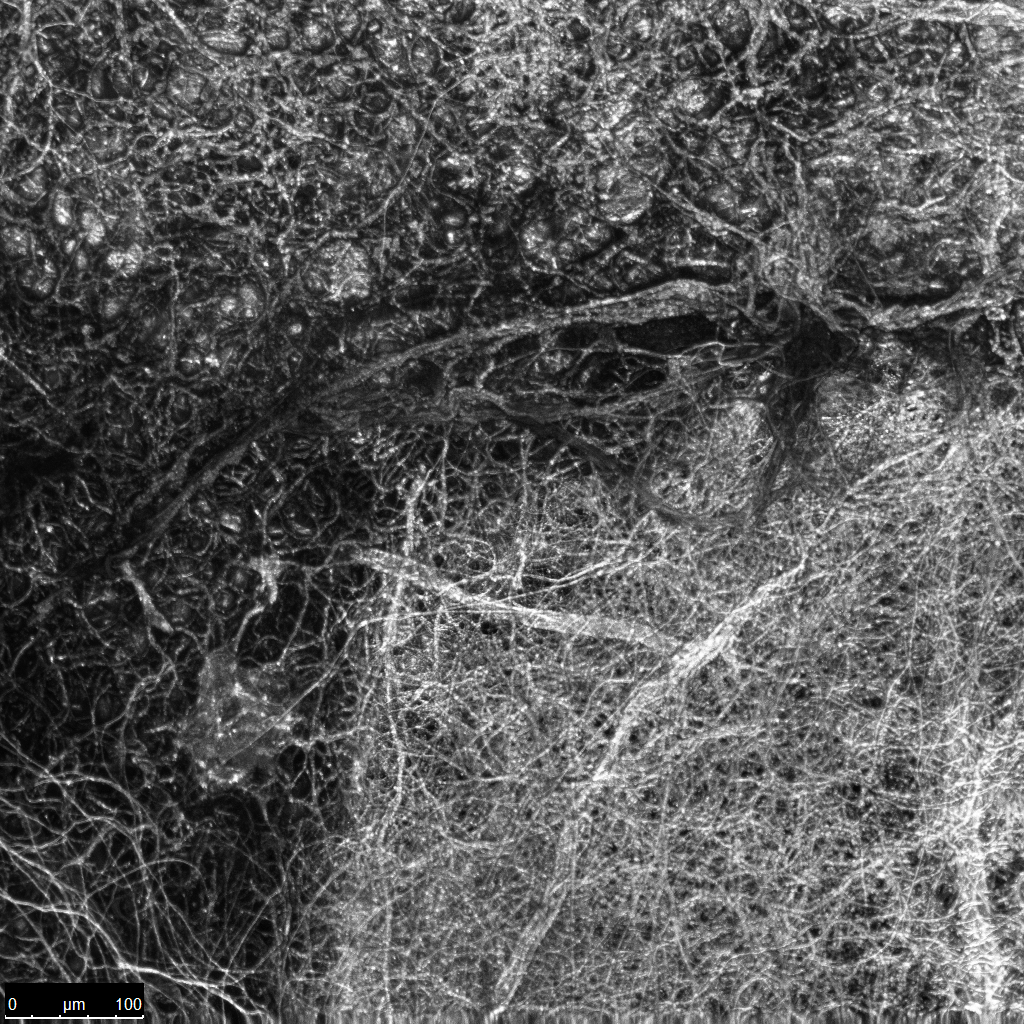

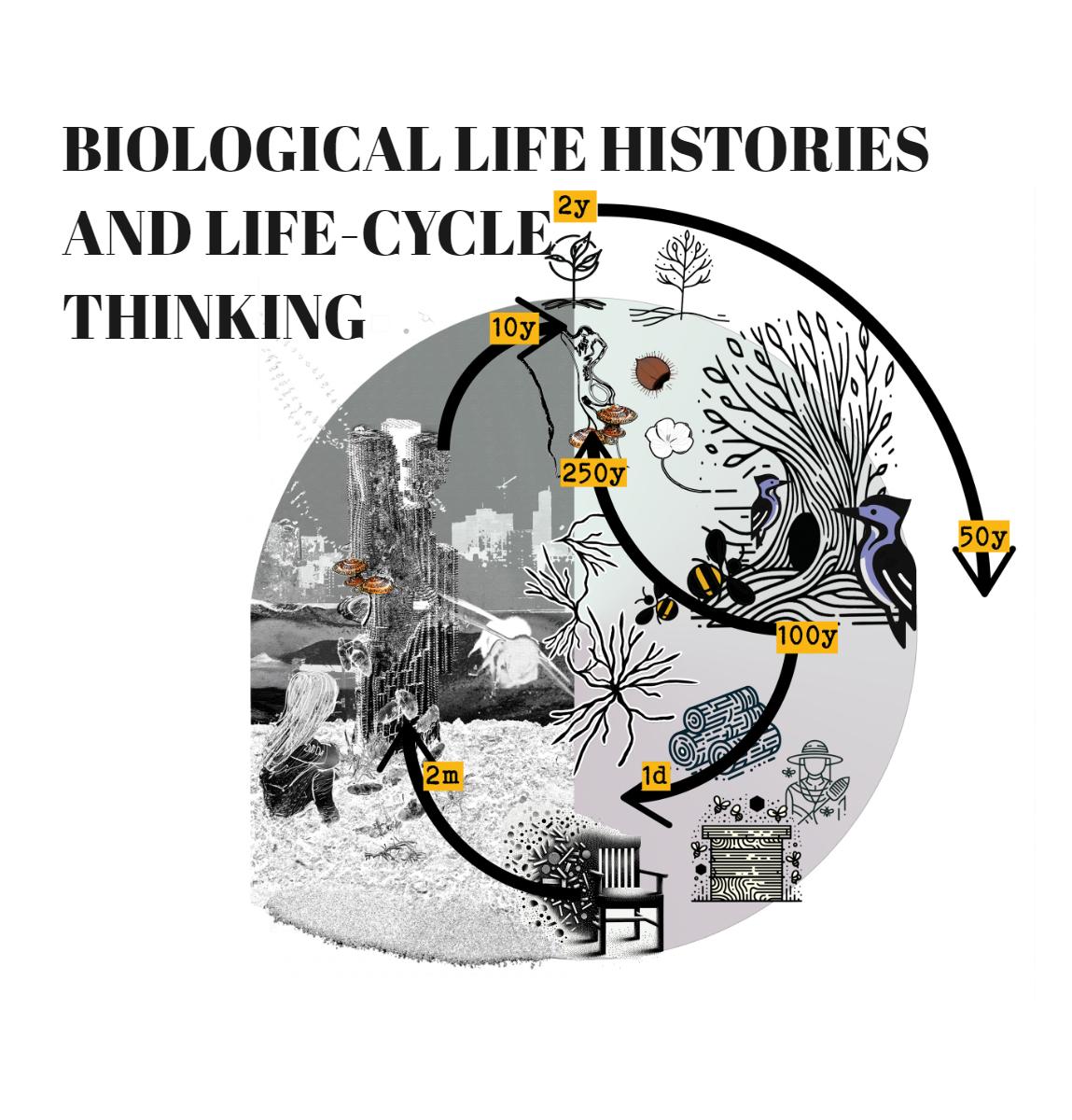

In general, my project(s) aim to bridge a growing gap between architectural production in all its scales and interspecies dependencies, especially amongst microorganisms, insects and us humans. Although environmental concerns appear to be acknowledged in the construction industry, the profession still exhibits a deeply ingrained extractive nature in its activities and remains far from recognising true multispecies entanglements. Today, science tells us that healthy microbial environments are vital for all life and that our built environments often suppress microbial diversity. Such an imbalance has implications not only for human health but also for biodiversity at large. My work seeks to reconnect design with the (for us humans) invisible relationalities occurring at such ecological niches through biohybrid materials and methods.

A central focus of my work has been on the nesting habitats for bees, both semi-domesticated (like honeybees) and the wild ones. While bees often thrive in urban environments compared to pesticide-exposed rural areas, they suffer from a lack of suitable nesting spaces. Many human interventions have sealed or eliminated natural substrates like deadwood and exposed soil, cutting off habitats bees have co-evolved over generations.

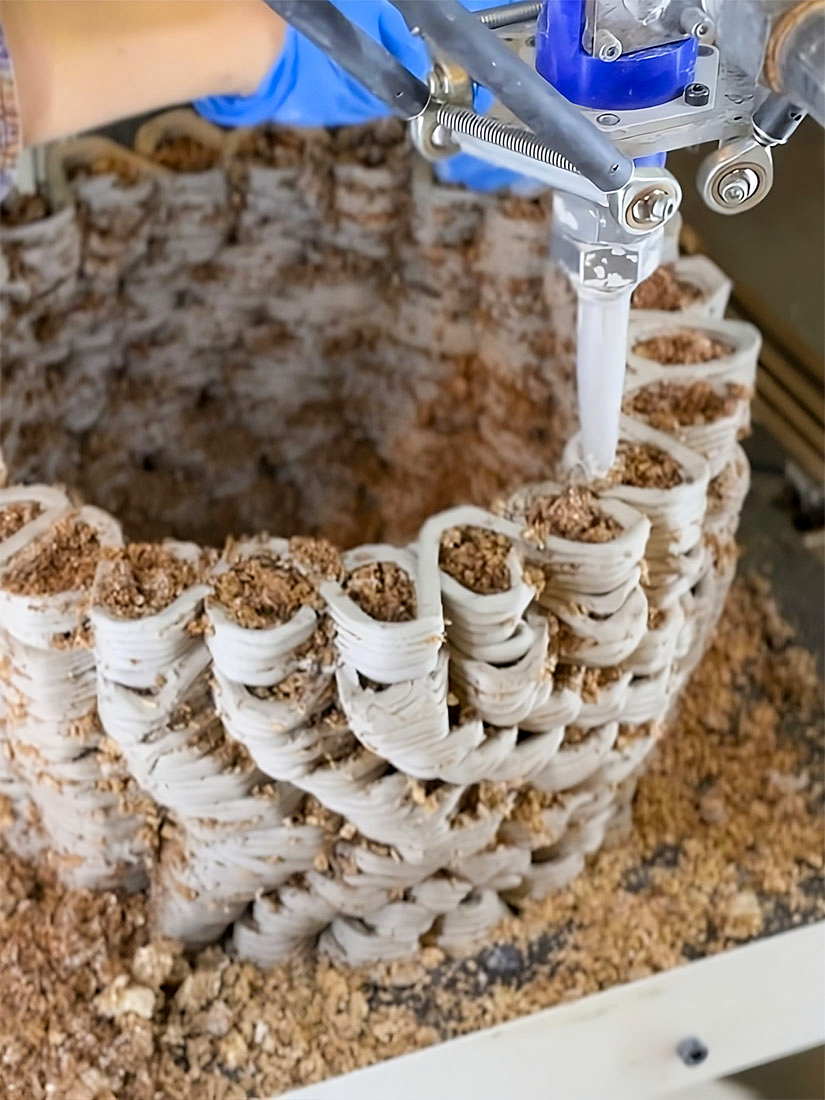

During my PhD, I focused on honeybee nesting enclosures, aka beehives, using fungal biofabrication and 3D printing to create lightweight, insulating, and biologically active hive structures. The digitally crafted scaffolds have been designed not only to house honeybee colonies but also to support mycelial life. Over the years since 2018, I have developed a framework for growing hives that sustain both fungi and bees. This work has also been supported by multiple distributed design programs, including exhibitions at the Respond Festival in Copenhagen, a 2-week residency at 3D PrintHuset followed by an exhibit at the Copenhagen Maker Festival 2018, a distributed design award that gave me a permanent exhibition space at the Vienna Design Week 2019, a mobility grant that took me to Fablab Budapest in 2022, and a recent WASP Award.

Curiosity about relationality

My journey began not necessarily with material curiosity but with an ecological connection. In 2018, while working with smart materials and 3D printing at the Artificial Life Lab, I became increasingly disillusioned with engineered thermoplastics. Although engineered thermoplastics are responsive and precise, they felt out of sync with the tactile and organic world of bees.

Then I came across Paul Stamets’ work showing honeybees interacting with mushroom mycelium. This shifted everything. I saw fungi not just as a material but as a living system with its intelligence. Despite initial skepticism from peers (“Why bring fungi into beehives?”), Stamets’ later research on mycelium’s health benefits for bees supported my instinct (nature paper)

Biohybrid Beehive Design

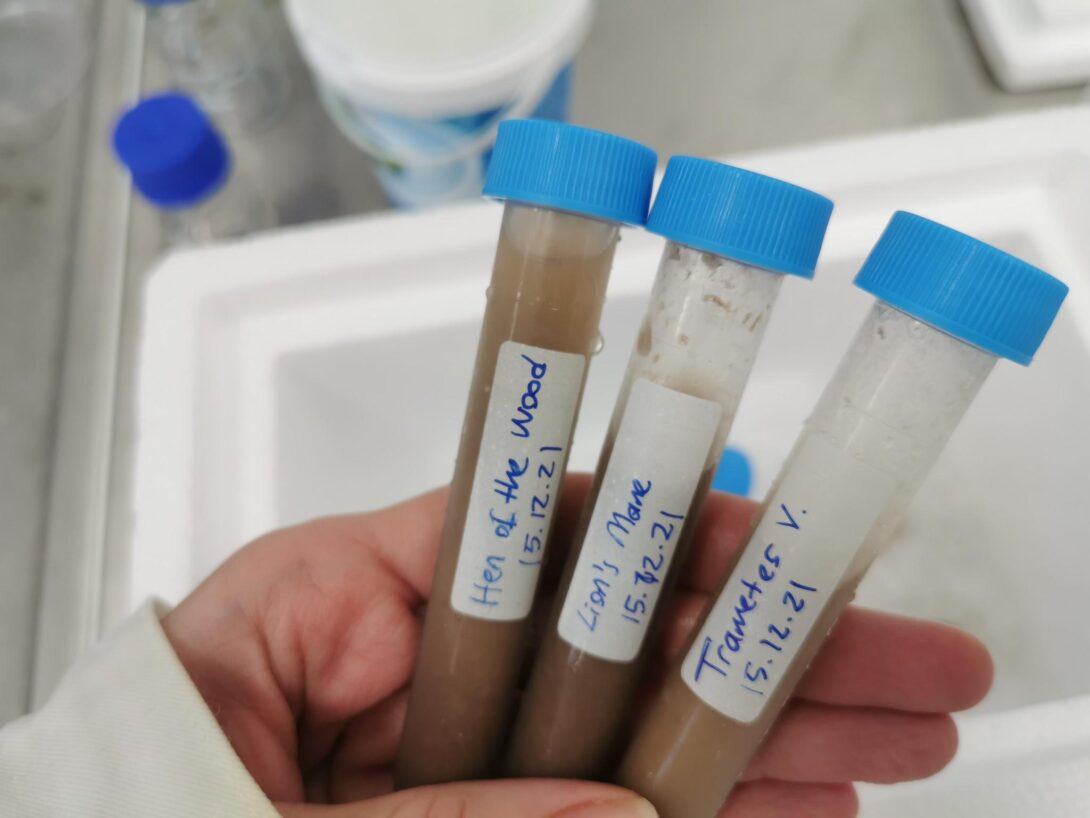

This realisation led me to grow beehives from mycelium—experimenting with both inert and living forms. Mycelium offers diffusion-open insulation, potential for medicinal properties, and eco-friendly biodegradability. Followed by an exhaustive marathon of bringing together wood particles and thermoplastic composites and woodrot mycelial fungi, I decided to experiment with replacing the thermoplastic with clay.

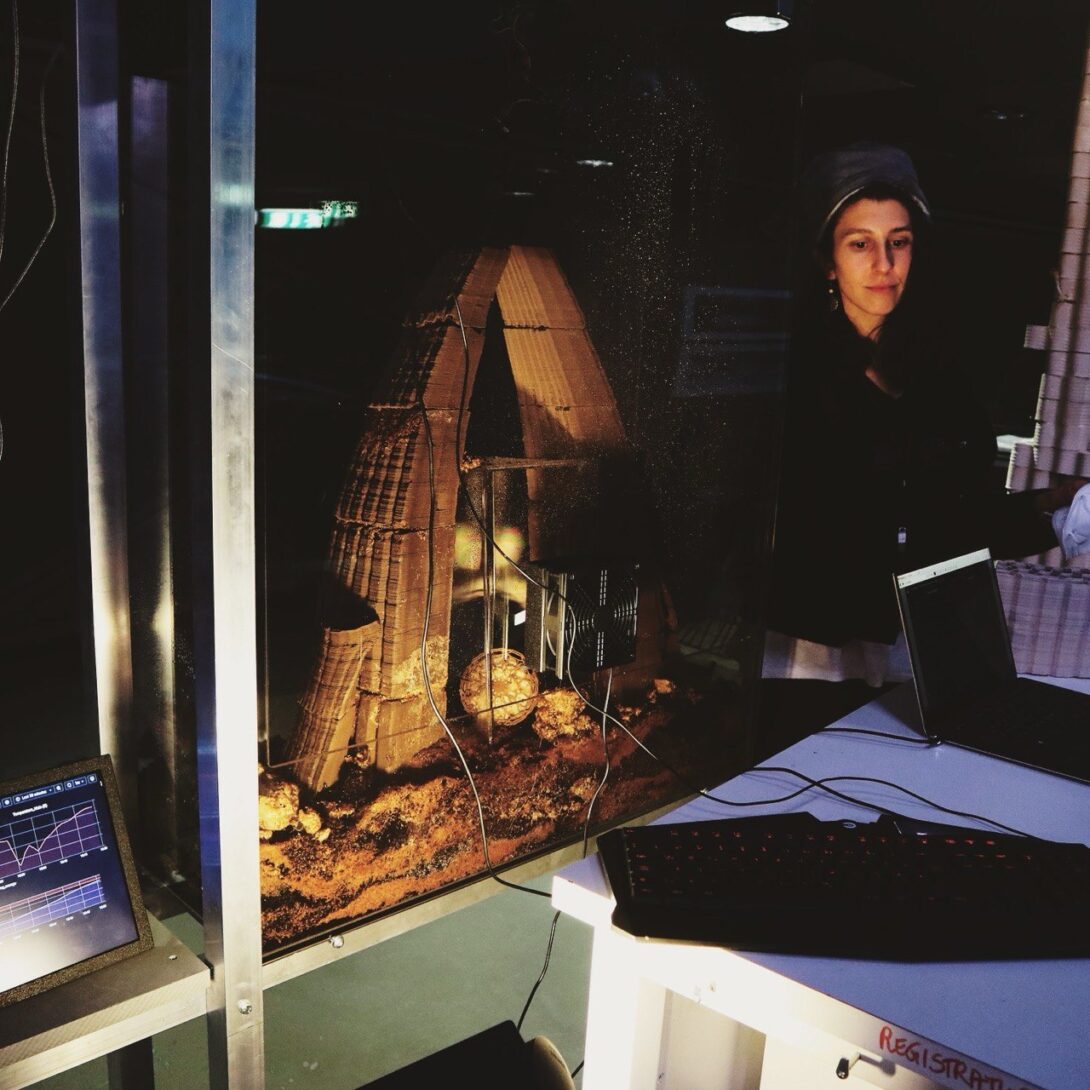

At Kunsthaus Graz in 2021, I presented “The Living Arch”, a 3D-printed mycelium-clay installation with embedded sensors to reveal its living qualities. It gave visitors a direct, sensory experience of what living architecture could be. This event was the second time I worked with a WASP machine, an LDM 4070 at the Institute of Architecture and Media, TU Graz. Julian Jauk, a post-doc researcher specialising in advanced clay 3D printing, introduced the machine and clay nuances to me back then. He has been developing the Termite plug-in for Grasshopper3D and I had the privilege to use the pilot versions 🙂

More bees..

In the meantime, I began exploring mycelium’s role in wild bee habitats and other species interactions, choosing strains based on local ecology and biochemical traits. This exploration started after a really fascinating nesting event happened on the balcony of the shared flat i was living. My flatmate called me to ask if I had drilled the mycelium piece that I have been drying in the middle of the balcony table on that sunny day, while she was sending me pictures of the tiny big mound of dug out wood particles in front of the piece. It was a Violet Carpenter Bee (Xylocopa violacea). She dug out her tunnels to leave her eggs.. Watching this happening inspired and excited me as much as I felt during my masters thesis where I watched honeybees building and populating my selfmade observation hives.

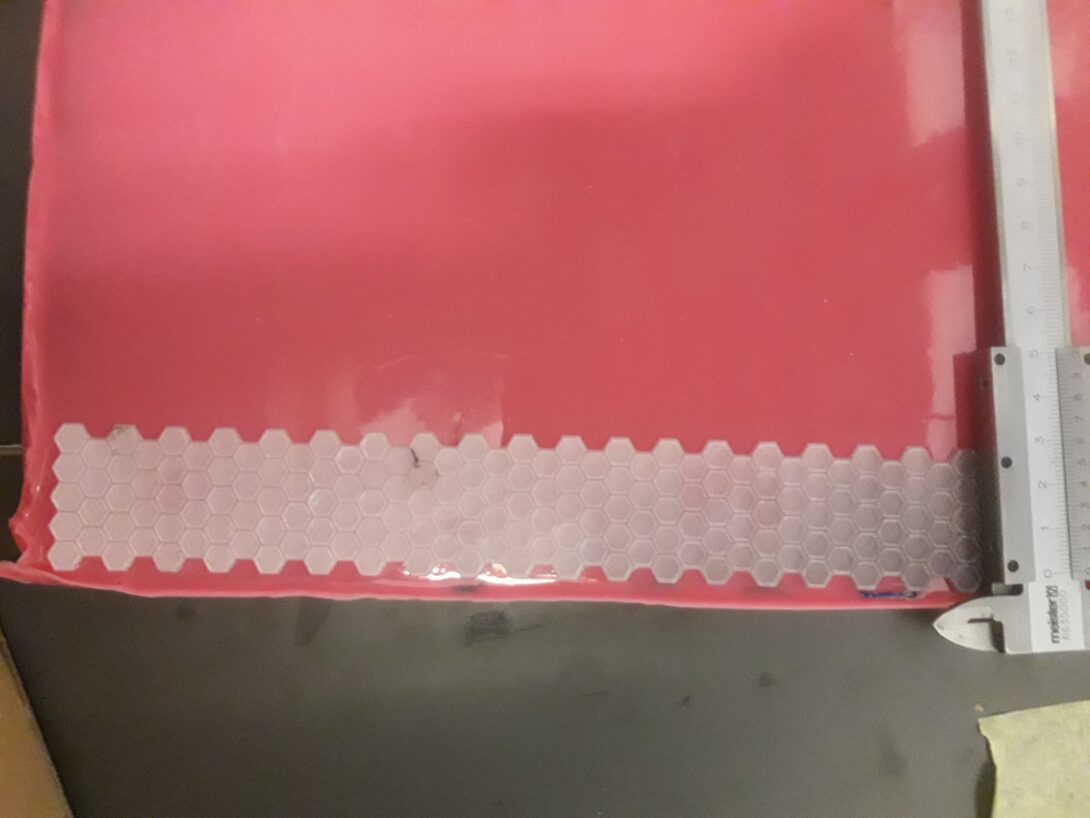

The habitat studies for wild bees emphasise and aim to raise the awareness for need for ecological specificity and long-term mutualism amongst many wild organisms living around us. Removing, replacing, “cleaning” seemingly “dirty” items from our environment can have detrimental effects on these ecological connections. Additionally, I experimented with various morphologies more suitable for making wild bee refugees in scales and module which are easy to handle. One of the images that I used while applying for the WASP residency showed a clay module with living Turkey Tail mycelium, removed from its site after spring and summer months of being installed on a soil mound surrounded with wild plantation. This piece was unfired clay with active mycelium and was completely transformed by ants in the region.

Multispecies Architecture and Its Challenges

Designing for more-than-human worlds means rethinking the role of architecture. It’s not enough to add fungi or insects as afterthoughts. True multispecies design requires integrating ecological needs from the very beginning.

This also challenges how we represent architecture—especially how we draw boundaries. Traditionally, walls are defined by a dashed line with a fixed thickness. But when designing for wildlife, we need to consider variable porosity, enabling other species to find habitat within or through those boundaries.

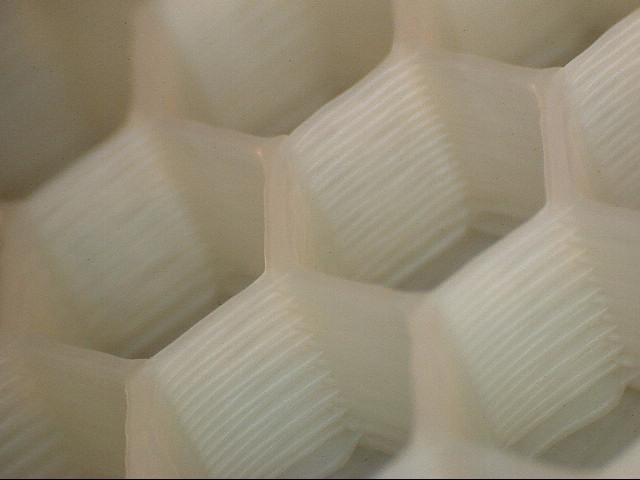

In the case of western honeybees, these needs have been documented in both ecological literature and traditional beekeeping practices. But they also open opportunities for experimental designs that allow for empirical testing. Structures must account for loads of up to 100 kg, insulating cavities of approximately 40 liters, and modular configurations that support spatial adaptation and repair. Materials like mycelium composites fulfill these criteria by welding parts together and forming air-trapping porous volumes. Fast-growing fungi such as Pleurotus pulmonarius minimize contamination during the first fabrication phase, while slower-growing species enable the cultivation of more intricate microbial relationships.

The Role of Mycelium in Sustainable Design

Mycelium challenges the idea of centralised, inert material production. It thrives on local, circular systems and responds to its environment in real-time—breaking down waste, emitting volatiles, and creating microbial highways. In my work, this becomes an ecological architecture where mutualisms can emerge: bees maintain the fungi, fungi insulate the hive, and bioactive compounds are produced.

In the HIVEOPOLIS project, we explored how these dynamics could work in real-world settings. While proving such complex interactions in a short field cycle is challenging, even partial results show the transformative potential of integrating living systems into architectural design.

Addressing the Ecological Crisis Through Habitat Rehabilitation

We are facing a collapse in biodiversity, driven by monoculture farming, urbanization, and chemical use. By restoring nesting infrastructure and microbial continuity, we can begin to counteract this loss. Replacing harmful materials like Styrofoam hives with mycelium-based alternatives is one step in the right direction.

Open-Source and Community Engagement

From the hacker space Labitat and close connection to Copenhagen Maker to Vienna Maker Faires to Fablab Budapest, I’ve shared methods and designs openly, with an intention to invite for collective exploration. My passion for the maker community engagement never got lost and now I can bring this passion to the Insect Worldings Association, which is a non-profit organisation we formed to host the I.N.S.E.C.T. Summercamps and its associated events as key platforms for this—bringing together researchers, designers, makers and citizens to learn and build in a multispecies world. Distributed Design community is a perfect network which can heavily support one of our main foci “Critical Making”.

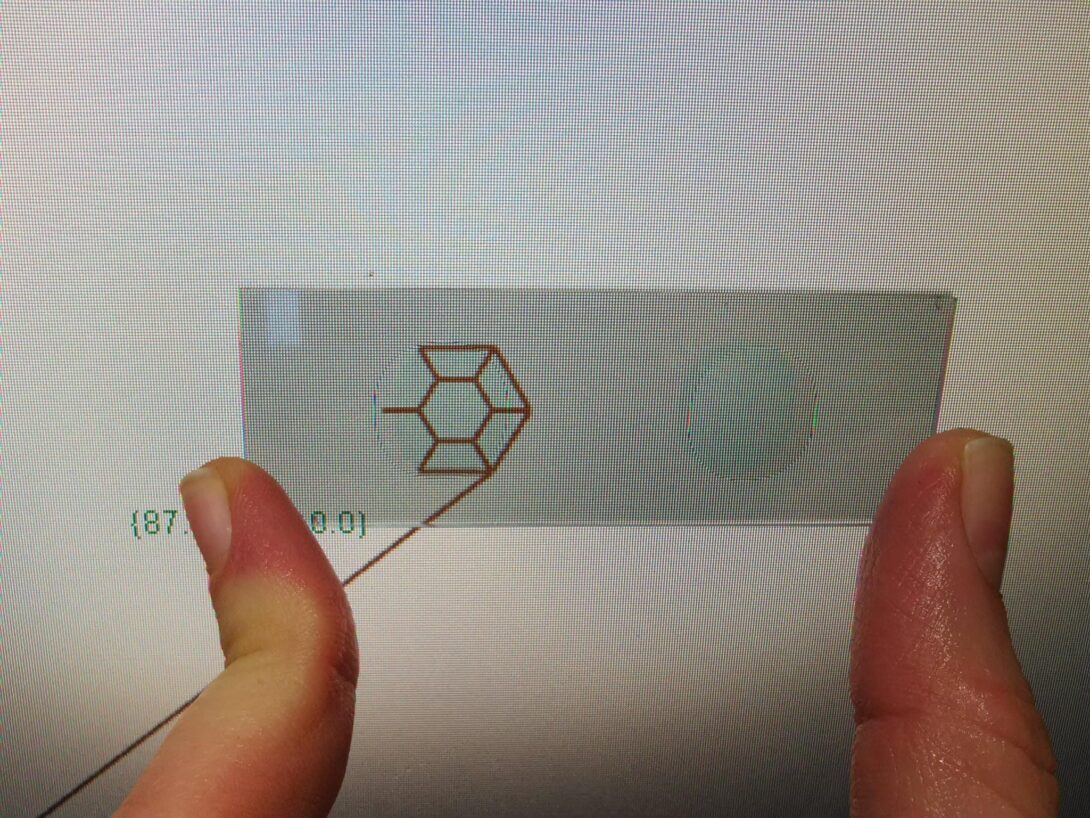

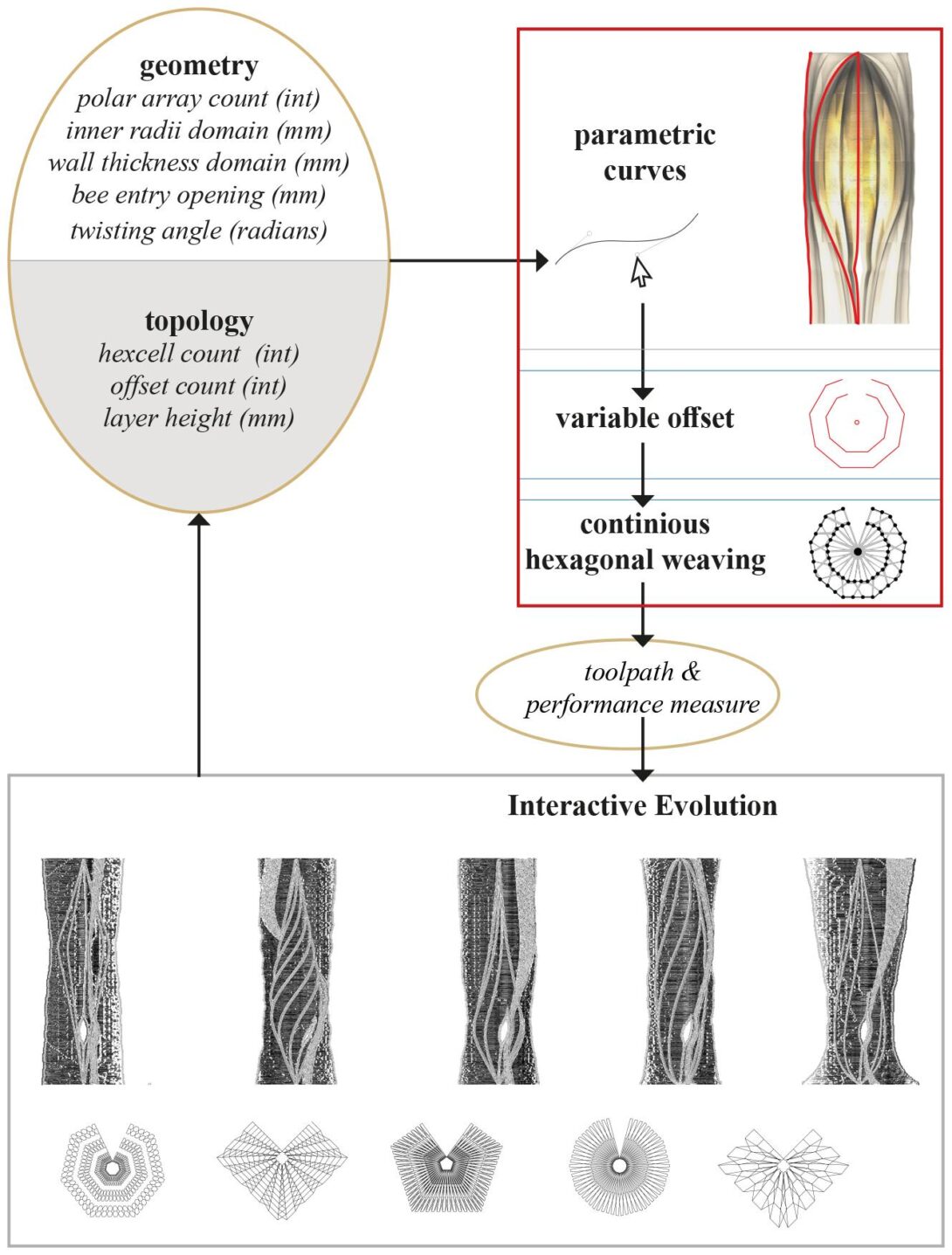

How I Model the Hive

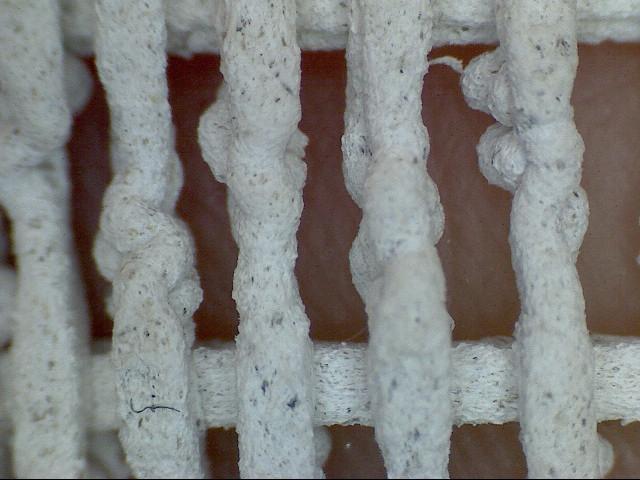

I use both hand-drawn intuition and parametric design in Grasshopper3D to shape hives with varied porosity and form. Implicit mathematical curves and genetic algorithms help explore form variation efficiently. My hex-weaving code generates continuous and spiralising polyline patterns that adjust filament distribution and support fungal colonisation.

The toolpath generation algorithm I developed, “hex-weave-gen”, allows creating hollows, pores, and modules, quite quickly in full fabriaciton resolution, which can host more than just honeybees but different insects and microorganisms. I am now focusing on specialist wild bees who need shelter in urban ecosystems and adapting the overall morphologies to 3D membranes made of topologically interlocking geometries such as scutoids.I shared all the digital models, processes as well as the fungal fermentation methods in an instructables post which allowed me to reach out to a larger maker community.

What Did the WASP Award Enable?

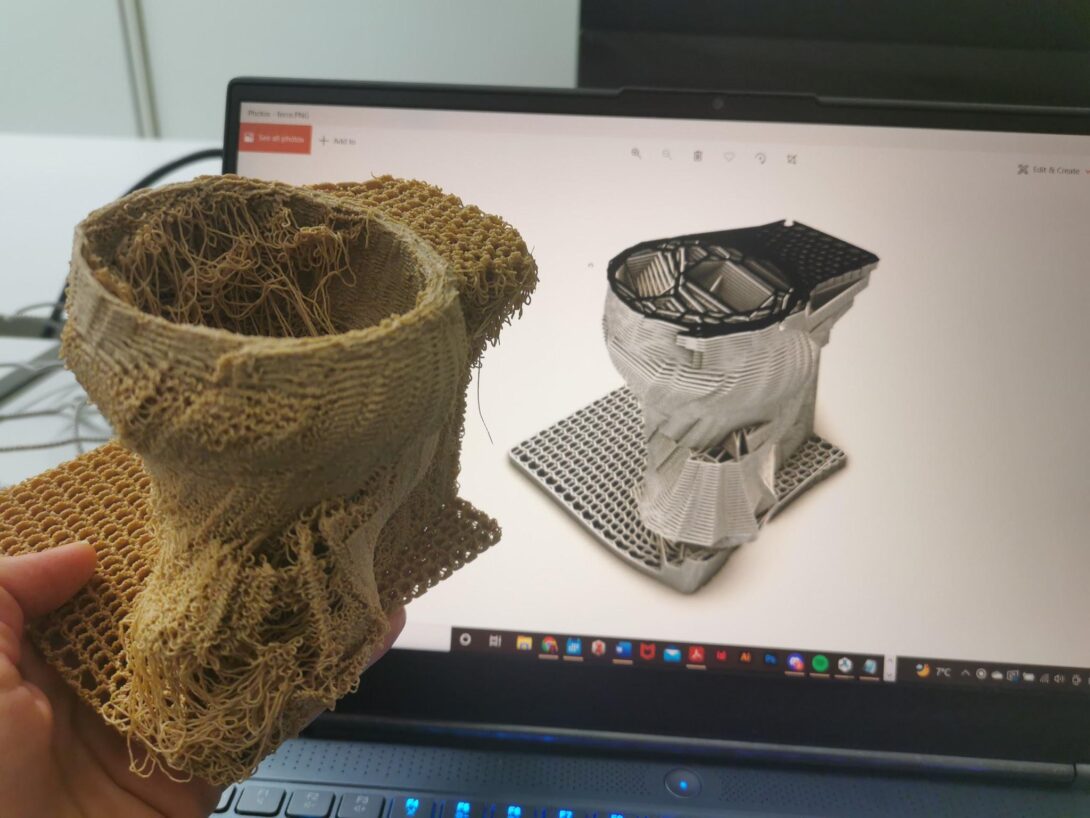

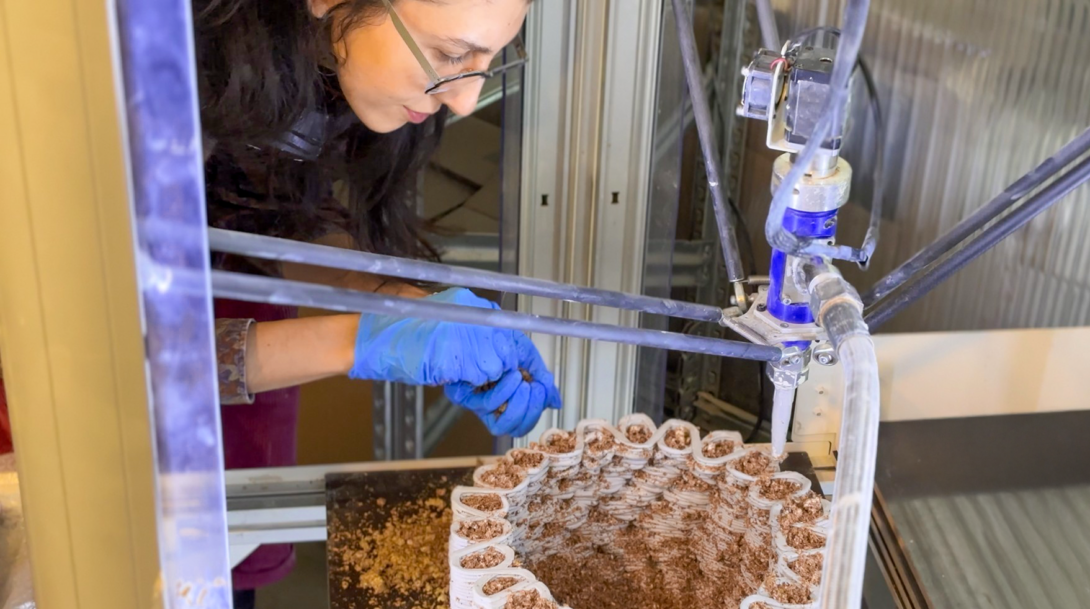

My WASP3D residency was a research residency rather than a design production sprint, as I spent most of my time experimenting with mixtures and risky toolpaths. During my time there, I aimed to refine the structural properties and material compositions necessary for the biological integration of the scaffold system that I developed. I knew that I would work with experts and interested people who are totally immersed in this additive manufacturing heaven.

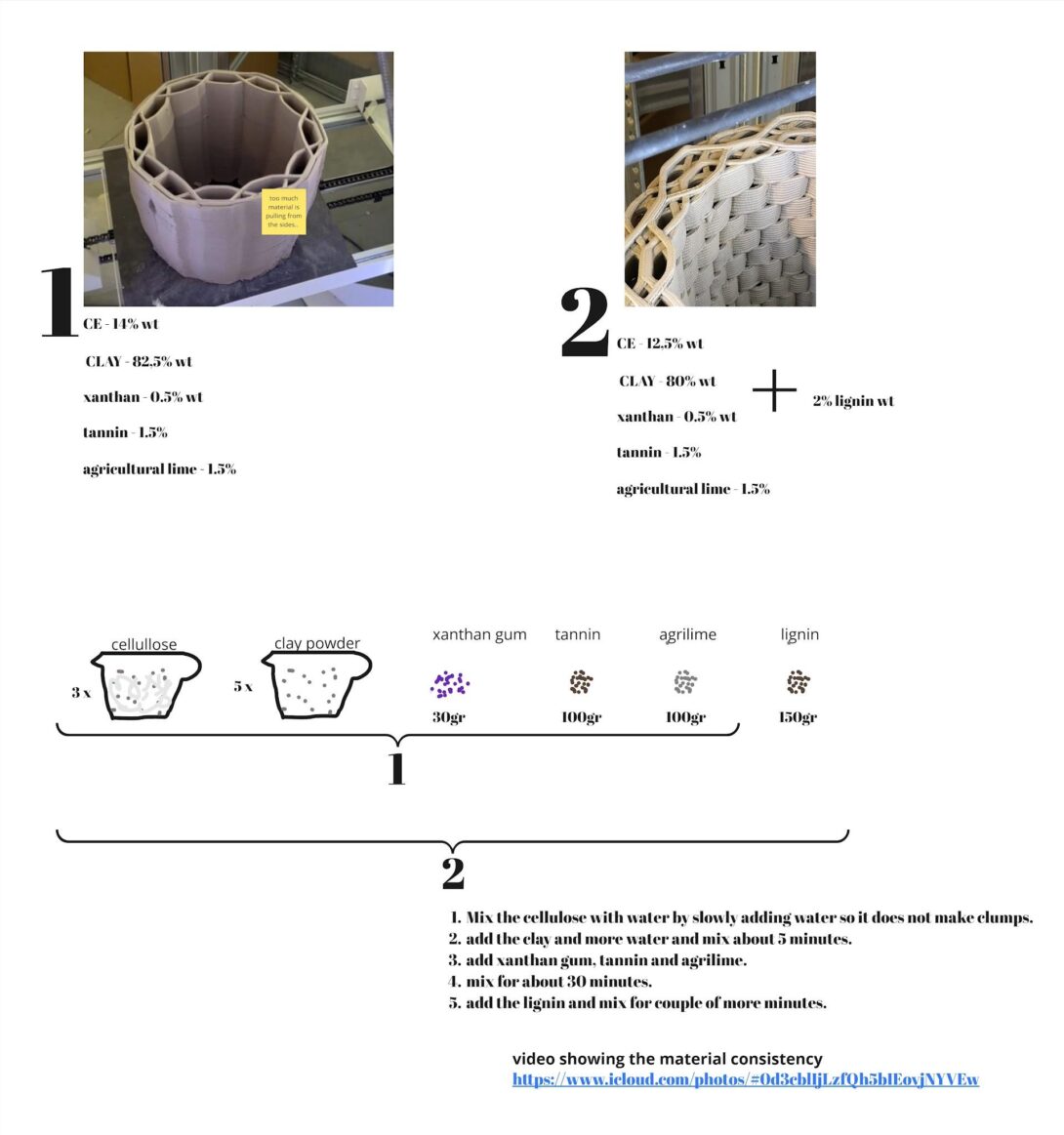

Key challenges of the scaffold design included layer adhesion while keeping porosity and material amount in mind, water retention and absorption for continuous wild fermentation of the fungal walls, and weather resistance against heavy conditions. During the residency, I had the chance to explore paste mixtures, which I could not during my PhD years due to the focus and financial resources of the larger EU project I was part of. The infrastructure, including the mixers and continuous feeding mechanisms, along with the technical support from my colleagues at the WASP3D hub, significantly enhanced my understanding of clay minerals as the primary adhesive and structural ingredient. This was made possible by Marco Ferretti, the clay expert and designer at WASP, who ensured that I had access to the space, tools, and knowledge in every possible way.

I also explored kraft lignin’s role in waterproofing and fungal interactions—especially for heartwood decay species for making the 3D printable paste. I enjoyed this incremental approach to making pastes, like in Italian bakeries (sometimes my mixtures looked like tiramisu and pizza dough 🙂 ) and the intuitive designerly freedom was all within reach. Initial nozzle issues led me to develop a new conical design. This was thanks to Massimo (the founder of Wasp), who stays there day until late evening and supervises all projects; he quickly crafted a nozzle for me from a leftover lid of a silicone tube and he told me that I should “be the material”. Adjusting water content and reducing cellulose improved printability and adhesion.

Using a mix of clay, cellulose, tannin, and agricultural lime, I refined two paste recipes suitable for liquid deposition modelling.

In the meantime, I had a chance to use the largest clay printer they have to produce a terracotta base column for the compostable hive modules to sit on. This was a spectacular learning for me, as the piece was printed as once without drastic failures.

What is more lasting for me is that I had a chance to see firsthand how architectural production and 3D printing technology come together in this hub. I also had regular discussions with Massimo, Francesca, and Marco about the Ithaca project and the potential role of bee habitats in it.

Coming from an academic background, it was extremely eye-opening to see the industrial relevancy but also sometimes redundancy of what I am doing. My artistic and experimental approach was never the final approach to the hive design and still is not. I took what I learnt to a co-design workshop at FabLab Wattens in Innsbruck, supported by FFG (the Austrian industrial research agency), to further work on the beehive.

What’s Next?

I’m continuing to test material combinations and fungal strains in outdoor settings, scaling up toward fully functional ecological architecture prototypes. I am very eager to bring the extrusion-based additive building method in inclusive, thoughtful and playful ways to my new projects. At the heart of all this work is a simple belief: that architecture can care, adapt, and support life beyond our own.

What I Took Away from the Distributed Design Award

The award reaffirmed the importance of collaborative, open, and experimental design practices. It gave me time and space to focus on improving key elements of the hive and connected me with a community of architects, designers, technologists, and makers who believe in a different kind of future—one is not subtractively but additively built, like wasps do (pun intended), woven with fungi, insects, and all the quiet life that sustains our world.

Links:

Social media: @asyimut and @insectworldings