“Every crisis presents us with an alternative.

Mandatory for movement. Towards innovation. On to the counter-move.

It does not allow inertia, wait, routine.”

Silvana Annichiarico

This quote from Silvana Annichiarico, architect and design curator, refers to the crisis and encourages us to take action. However, what we are experiencing today is a “polycrisis”, something way more complex and impactful.

The word “polycrisis” appeared during a panel discussion at the World Economic Forum’s Annual Meeting in Davos in March 2023, used to describe a series of interconnected and interacting threats: the knock-on effects of the pandemic, the global political unrest and conflicts, the rising of social and economic inequalities, the climate change and the subsequent ecological disasters.

One year later, since then, things seem to have gotten even more complicated. And questions arise even more heavily. Is there still an alternative behind this multifaceted planetary crisis? What’s the role of designers in creating a resilient society?

Resiliency and the fashion realm

Resilience is a word that has long been mistreated. Boris Cyrulnik, neuropsychiatrist and ethologist, was one of the first to borrow the neologism “resilience” from metallurgy to social sciences, to entail the process that allows human beings to activate inner resources and to re-emerge from traumatic events without being crushed by them.

In product design, resilience is the ability to create products that can perform and adapt effectively in changing environments and quickly recover from disruptions.

In short, products able to transform, either being flexible or adaptive to different needs and contexts.

When it comes to the fashion sector, it means that garments or accessories must be thought of as adaptable and absolving multiple uses in consideration of different consumer’s needs that change often and quickly, due to fashion marketing on one hand, and attitude on the other.

Incorporating resiliency through transformation can lead to integrating the urgency of a change into the design process, either it is aesthetic or functional aspects.

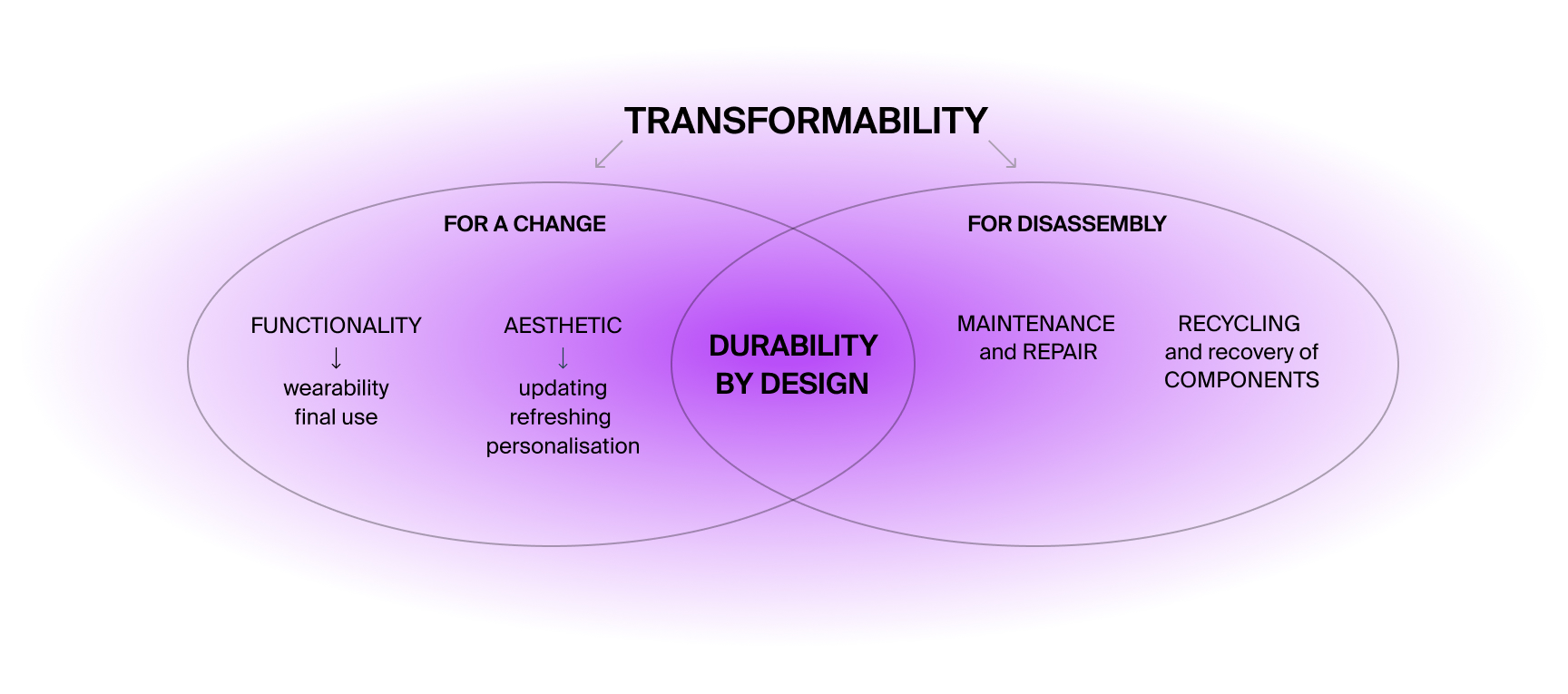

The multiple faces of transformability

Aesthetic changes generally arise from a personal need to change style by updating it according to the latest fashion trends, the current individual tastes, or our changing personality in different social contexts.

Fashion theorist Malcolm Barnard explains it well when he says “The dress is not reflecting social and gender changes. Rather, it is those changes; it is enabling those changes and it is the means by which they are made possible.”

A type of transformable clothing that was very widespread in the early 1900s was the double-faced in which reversibility could be obtained by using backless fabrics characterized by a different appearance on both sides and usable in both directions, or by coupled fabrics worked with “english” stitching that allow the complete reversibility of the garment.

Among others, Gucci has instead recently used this approach in knitwear to transform with a single gesture the most basic colours and patterns of cardigans and sweaters into unmistakable patterns of Double G monograms.

Using the same double-knit construction, but pushing the concept of transformability a little further, is Stone Island: the external face of their Ice knit sweater is made of an exclusive thermosensitive yarn that drastically changes colour if exposed to the cold, while the internal one is in pure wool.

Another common way to intervene on aesthetics is customisation, the most traditional way we know to refresh garments’ style to make them more personal and unique.

Today customization is often integrated into the purchasing phase as a co-design practice in which the user selects components or defines some characteristics of the final product, taking an active role in the design process.

The Italian fashion brand Golden Goose is pushing this concept even further making this practice its own signature and creating customisation opportunities during the post-purchase phase, by adding extra components – such as studs, crystals, patches – and the manipulations of materials. Their boutiques are equipped with workstations where people can spread their creativity on personal personalisations and embellishments for sneakers, bags and accessories.

In fact, since the first decades of the 20th century, transformable clothes have been promoted above all from a functionalist perspective by virtue of their versatility, interpreting the ideals of modernity of Western fashion.

Functionality is the second main purpose for a change and when it comes to functional changes: we can exploit the transformational design technique to adapt the fit of clothes and solve problems related to growth, loss or increase in body weight, or to respond to particular needs related to physical disabilities. In a word: body inclusivity.

A great example of this concept is the collaboration between the designer and researcher Bolor Amgalan and Open Style Lab, a non-profit organisation dedicated to creating functional wearable solutions for people with disabilities.

The outcome is Softable, a jacket co-created with Robert, a resident of a rehabilitation centre for disabled people in Manhattan, that maximises independence from operator assistance in dressing routine and enhances self confidence in social interactions.

Prototyping was carried out in several phases in order to develop the final jacket model which takes into account the user’s reduced motor skills and provides a rear closure so that the garment can be worn frontally and closed with a lace system avoiding zips or buttons.

When sourcing the fabric, due to Robert’s disability which forces him to constantly sit in a wheelchair, the properties of moisture absorption, elasticity, as well as good breathability were taken into consideration in addition to the inclusion of folds with a mesh fabric for ventilation and extra space for movements in total comfort.

As they say at Open style lab, “when design stems from necessity, innovation is always the result”.

Functional changes can also be defined by the need to be quickly adaptable to emergency situations or outdoor environments, or even to be ready to pack your bags and leave with volumes and weights reduced to the bare minimum.

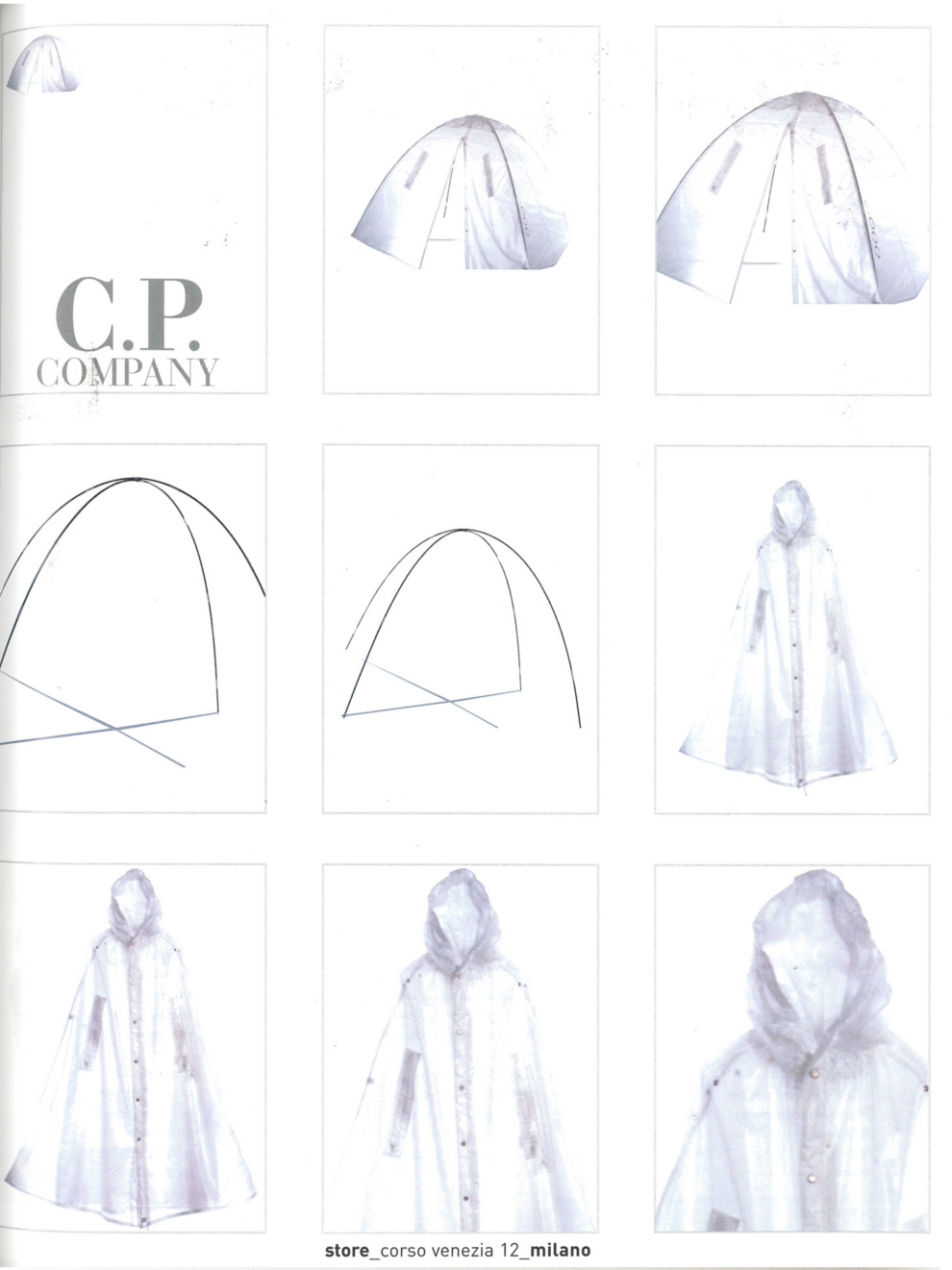

In 2000 Moreno Ferrari, C.P. Company Designer from 1996 to 2001, developed a highly conceptual line called “C.P. Company Transformables”. This innovative series consisted of dual-purpose garments that could be “transformed” almost instantly by simply pulling a toggle or a zipper. The project included clothing that turned into camping tents, sleeping bags, backpacks and even a kite.

Heir to this approach and to the love for sportswear aesthetic, is the English designer Craig Green who has proposed a series of oversized down jackets for Moncler, a special design project that can be rolled up like a sleeping bag. Afterwards, with his personal label, he further explored the concept of pliability on a more commercial level, designing everyday items, like skirts or jackets, to be easily folded in trendy pouches or bags.

In addition to changes related to our physicality, we experience even more frequently the need of new functions and quick adaptability because of our lifestyle – such as moving from different work contexts and social environments (ie. from formal to relaxed work context, from an early morning meeting to a night out with friends).

In this case, clothes can be transformed through a sort of performance by being stretched, turned over, unfastened or buttoned.

One of the most interesting contemporary brands surfing on this wave is Flavia la Rocca, an Italian designer who investigates the concept of modularity by creating few pieces combined together in multiple ways to compose different garments, such as the “The ”Not Just a Dress” Set. The pieces are interchangeable and versatile and can transform into dresses with modular lengths, tops, skirts, bandeaus and even bags allowing customers to create wardrobes with less thanks to simple buttons, drawstrings or zips.

An interesting example to mention regarding transformational accessories is the experience of the designer Linda Zamboni for the re-edition of an old 24-hour briefcase that the brand Pineider wanted to update. In this case, after reviewing the internal compartments to accommodate laptops, the ambition was to make the bag multifunctional, by working on portability and adapting to accomplish the multiple needs of contemporary users. By developing a single metal component, with very simple gestures the two shoulder straps could be used to hold a briefcase and a backpack.

Weather and seasonal changes are other two external factors that fashion has tried to face by giving extra functions to garments to make them transeasonal.

Marfa Stance is an English brand, specialising in outerwear with silhouettes that can be easily integrated with detachable elements such as collars, hoods and linings that can be designed with an online configurator. The peculiarity of this project is being at the intersection between multifunctionality, ability to adapt to different climates or seasons and being ageless and genderless.

In the perspective of the circular economy, disassembling and repair are two key-strategies along with the possibility to recycle and recover components.

Design for disassembly is a strategy that considers the weak points in the early stage of the design process: including repairability “by design” opens up opportunities for personalisation and upgrading through time, easily to be implemented by the users themselves.

One of the most famous examples is the bag retailer and pioneer in circular fashion Freitag, who creates unique items from upcycled truck tarps. The Zurich-based brand has integrated in its commercial offer a repair service and repair labs in their store. Moreover, in contrast to the market, one can also request spare parts through their website and shops, such as plastic buckles, metal snap hooks, rings, studs, buttons, giving the opportunity to repair their products independently.

Recycling sneakers is one of the most difficult challenges because of the different materials and the production techniques – such as stitching, glue, binding making the shoes almost impossible to disassemble and recycle.

Nike has long started to invest in the design of easily disassembled shoes, in 2004 they launched Zvezdochka designed by the award-winning industrial designer Marc Newson with a flexible moulded outer cage and a removable sock-like bootie. More recently, thanks to technological innovation, Nike has presented a series of advanced sneakers, such as the Link Series made up of three interlocking modules connected without glue that can be disassembled and stored in Nike stores that offer the Recycling & Donation service.

In 2023, the Link Axis will be launched, made with a 100% recycled polyester Flyknit upper designed to fit the 100% recycled thermoplastic polyurethane TPU outsole obtained using waste material from airbags.

Whether transformability is aimed at implementing an aesthetic or a functional change or at recycling materials, it always deals with prolonging the life of the products or at least of the material used: through this multifaceted circular design technique, designers can be an active part in preventing the rapid obsolescence of their products remaining unused in our wardrobes or ending up in landfill.

And if anyone doubts the commercial effectiveness of transformable products, we can confidently say that, on a practical level, versatility, multifunctionality and customizable products are winning features both for a brand’s offer and precious ally in the life of the users. After all, change has always been the founding, timeless, value of fashion.

by OpenDot and Linda Zamboni, teacher in Sustainable Fashion at Istituto Marangoni