Pjorkkala’s interdisciplinary team of designers has dedicated itself to finding solutions for water purification in areas with inadequate or deficient public water supply, placing the role of the designer at the forefront.

The Pjorkkala group, which consists of young designers Žan Girandon, Pia Groleger, Luka Pleskovi?, Ema Kapelj and Zala Križ, as part of this year’s Biennial of Design BIO27 Supervernacular – the oldest biennial in Europe, organised by the Museum of Architecture and Design in Ljubljana, Slovenia – under the mentorship of the Indian architect Shneel Malik, researcher of co-natural design and social entrepreneur, set about making prototypes for cleaning of polluted natural waters in Slovenia. Shneel Malik is a ceramic designer and author of the INDUS algae-coated ceramic tile project, which represents an innovative concept for water purification, and she shared her experience with young Slovenian designers as part of the BIO27 Production Platform.

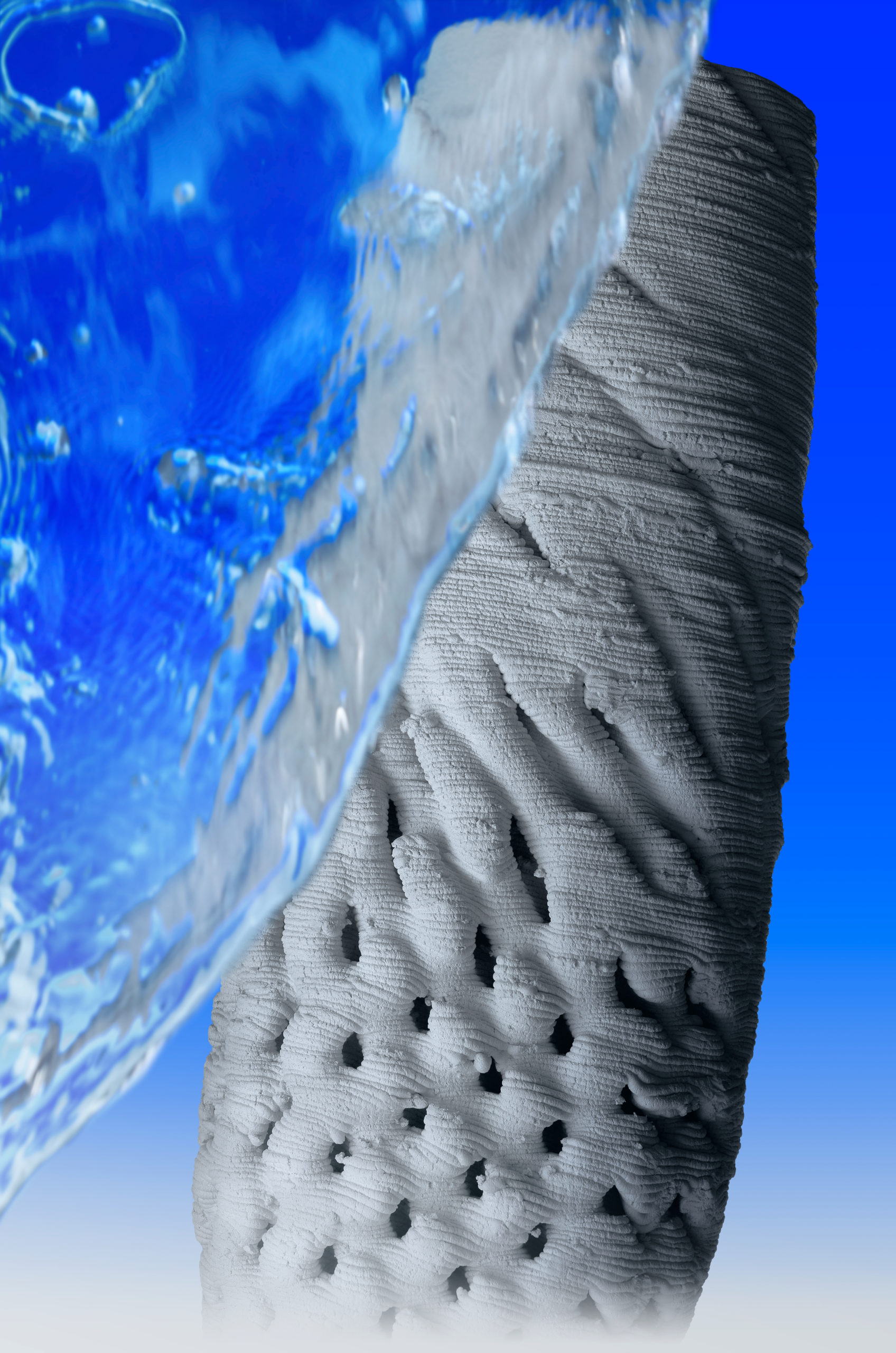

Making water filter with 3D printing clay.

Approximately 20 percent of Slovenians do not have access to a public water supply system, and even those who have it often prefer to use water from other, natural sources. In Slovenia, there is a general belief that water from spring sources and mountain rivers is clean, but since most of Slovenia’s territory is of karst origin, it is difficult to predict the flow of groundwater and its pollution, which is the result of agricultural practices such as excessive fertilization. “We decided to formulate the problem in a way where we as designers could have the greatest impact. We focused on the technological scope, reaching a solution and water quality,” explains Pia Groleger, and Žan Girandon adds: “For the pilot area of ??the project, we chose a location in the Triglav National Park, where the spring waters, contrary to public opinion, are quite polluted.”

Named after the Slavic rain goddess Dodola, the filter represents an affordable solution by combining the use of vernacular materials and practices, natural and physical phenomena, and modern manufacturing processes. Installing filter modules enables filtering bacteria-sized contaminants from the water, leaving only desirable substances such as minerals in the water. Dodola is made from a mixture of clay and organic substances, and it is fired in such a way that its porosity is greater. The gyroid structure, which accelerates water filtration due to the larger available surface area of ??the module, was created by 3D printing clay. By following the principles of Archimedes’ screw, however, Dodola can flow water through the filter by relying on the water flow in which it is installed, helping to operate autonomously in remote locations where there is no electricity.

Wood saturated with bacteria can no longer filter water.

The problem of contamination with E.Coli bacteria in the Triglav National Park led the designers to research possible vernacular principles that could be used within the limits of the location. This was followed by a narrowing of the focus to mechanical water filtration with two different types of materials – xylem tissue and porous ceramics. Tree sap filters out more than 99 percent of E.Coli bacteria. To create the water filter, they first used xylem tissue from pine and spruce wood, as xylem tissue allows water to flow while blocking most types of pollutants larger than 70 nm. “Spruce filters were very convenient for us also because of the prevalence of this tree species in Slovenia,” explains Žan Girandon.

However, such filters also have their disadvantages. They need to be changed regularly, because wood saturated with bacteria can no longer filter water. This ability is also lost when the xylem tissue dries out, making their production and implementation problematic. They have been replaced by ceramic filters, which are affordable and sustainable, and are also more versatile than xylem filters, as regular cleaning of the filtration surface maintains their optimal performance. The structure of ceramic filters has small pores that remove 99 percent of bacteria and sediments, prevent turbidity, but at the same time do not remove useful minerals from the water. “We made the ceramic filter by mixing sawdust, powdered clay and water in the right proportions. The prepared mixture was inserted into a 3D printer, with which we created a suitable shape. The resulting structure is then baked at 950 °C and soaked in distilled water for eight hours,” explains Pia Groleger.

Designed after beetles and butterflies

The form exploration process stems from material experimentation and began with the help of generative design and 3D clay printing technology. When making the filter, experimenting with shape was very important, which is a key part of this water filtration technique. The larger the filter area, the better the filtering effect. Jean Girandon: “Our goal was to create shapes that would retain water, improve flow and allow water to move upwards. Due to the utilization of hydraulic pressure below the surface, the underwater parts are designed in such a way that they enable faster absorption of water through the entire surface of the structure.”

In the creation of the water filter, they looked into biological forms from nature and ancient knowledge. To make the filter, they used a gyroid structure, such as is found in the exoskeleton of beetles and in the wings of butterflies in flight. The structure allows for increased water permeability and greater static strength. “Such a structure increases the permeability area several times, and the result is faster water filtration,” explains Pia Groleger. Part of the filter also represents the Archimedes screw, which flows water from a lower to a higher lying position. The water flow drives the rotation of the filter, so the device can be installed even in the most remote areas where there is no electrical installation. The structure is submerged below the surface, where the porous material filters the water as it travels through the ceramic wall. The water flow causes rotation, which allows the water to flow into the higher part of the module, where it leaves the system as purified drinking water.

Text: Smilja Štravs, Museum of Architecture and Design, Slovenia

Photos: Pjorkkala