Every year, 5.8 million tons of textiles are thrown away, about 11.3 kg per person (1). According to the EU Environment Agency, textiles are in 4th place when it comes to the negative impact on the environment and climate change, if only considering European consumption.

Clothing waste is indeed a huge problem.

Lately, the effect of our shopping habits is becoming more and more visible, from the shocking images of the Atacama Desert dumping ground to the artwork of Pistoletto’s Venus of the Rags, we all have came across this global challenge and we all have dedicated a thought to this, at one time or another.

Despite that, according to Fashion United research, in Europe only 12% of consumers consider sustainability particularly important in the fashion sector. Perhaps because this is considered a secondary problem compared to the meaning we give to fashion. More than ever, garments have a lot to do with people’s lifestyles, personality and sense of belongings, and they became a sort of “personality interface”. More than just functional goods as it used to be in the past.

Through clothes, the communication between our internal identity and the external world takes place, and wardrobes are inevitably subject to continuous updates and changes.

The turnover of products is closely connected to the turnover of social identity under the pressure of social media, together with the phenomenon of production delocalisation – which has led the cost of clothes to drop dramatically, creating easy accessibility and diffusion of fast fashion clothing.(2)

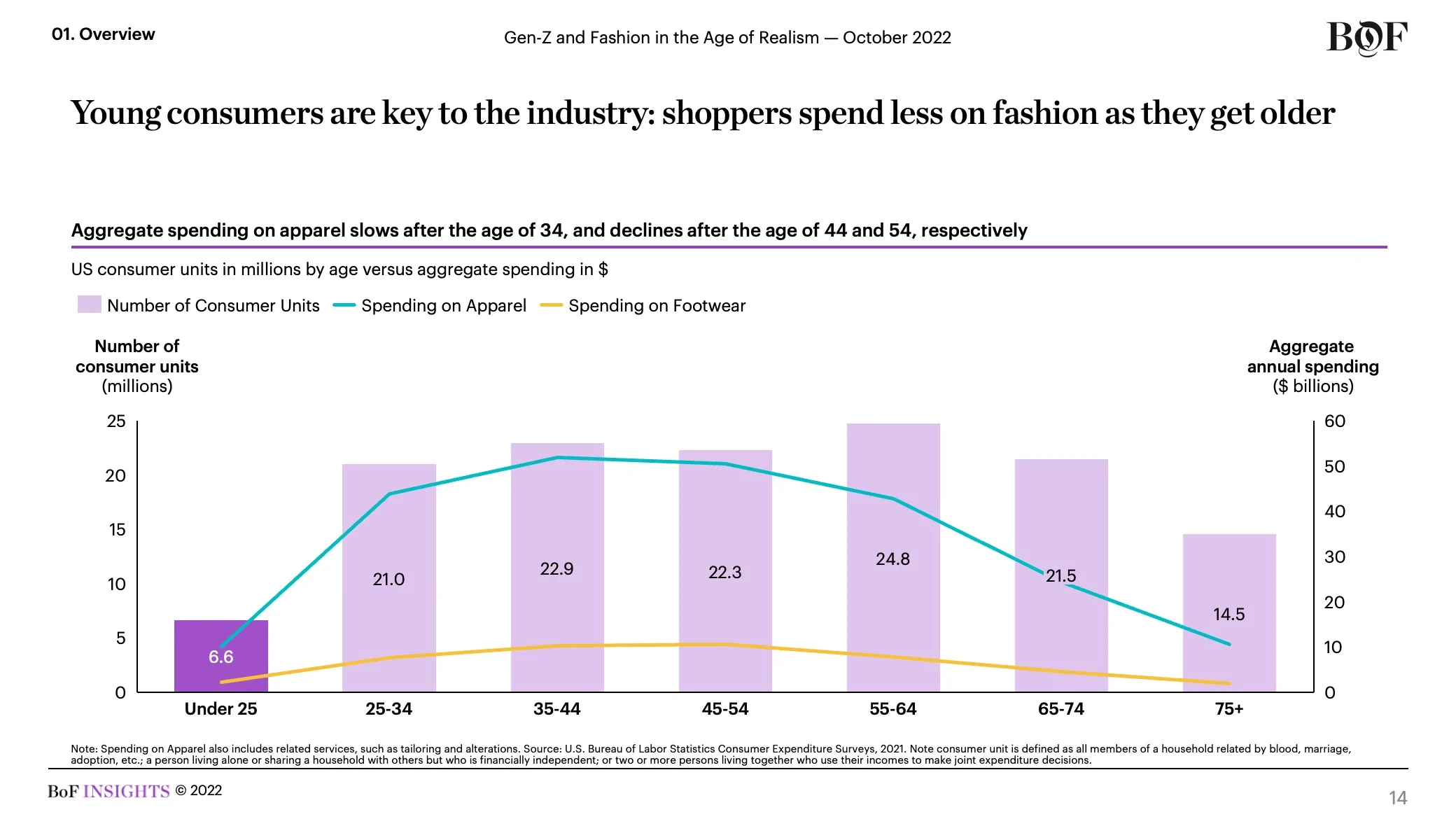

The personal purchase of new garments often transcend any other factor, but it’s interesting to notice that statistics report that after the 40s consumers are more inclined to buy less, probably because they entered a more aware phase of life.(3)

Having established the fact that the role of clothes in the lives of consumers has profoundly changed, it is even more urgent to fully understand the reasons why people decide to throw away their used clothing.

During our research and experimentation we found that the predominant reasons motivating premature disposal are mainly four:

- aesthetics, referring to those clothes that are irremediably stained or shapeless and are no longer in their original condition;

- functions, relating to functional damage that precludes the use of the clothing, such as tears or holes;

- use, when clothes are out of fashion or linked to a very specific occasion of use and therefore difficult to wear;

- life changes, referring to changes in the personal sphere, it involves those clothes that can no longer be used because they are out of size (weight gain/loss, pregnancy etc.) or because they are not suitable for a new environment (change of job/change of Country) or because they no longer reflect personal aesthetics.

In all these cases, from the consumer perspective, every time we get rid of our unwanted clothes we lose value. We lose valuable materials and, moreover, precious resources such as water and energy needed for the manufacturing.

In times of ecological crisis, being makers or fashion/textile designers with the ambition to work towards a circular transition and a more sustainable future, we should all ask ourselves how we might restore this value, raise awareness among people and increase the garment’s durability.

As in all challenges related to the circular economy, we believe that in the fashion realm the path towards the resolution lies in collaboration: on the one hand, consumers must become more critical and aware, on the other hand designers and brands should question and improve their design and production methods.

It is precisely by starting from disposal motivations that designers can understand how to extend the life cycle of products and design them so that they are more durable, from both a physical and aesthetic point of view.

By physical durability we intend materials, construction and components designed to resist damage and wear, whilst emotional durability considers the product’s ability to stay relevant and desirable to the user, or multiple users over time.

Within this frame, to understand how to set up our circular design practice, it can be of great inspiration to look at what has been done by pioneers in the past and what contemporary designers are currently doing to make a difference.

What follows is an exploration of circular design techniques that are radical approaches and far-sighted strategies of product design meant to make products last by having multiple life cycles.

- Upcycling/repurposing

Upcycling is a form of recycling in which discarded materials are converted into items of higher value than the original input, or discarded products are transformed maintaining the original purpose and improving pre-existing factors – such as appearance and functions.

Meanwhile, in repurposing, a product’s original purpose is altered but its value is preserved without the loss of material or appreciability.

Thus, clothes with stains, tears or holes can be recovered, as well as out-of-fashion garments or deadstocks.

In this instance we could immediately mention Jean Paul Gautier with his 1980 collection where car leather and cans were turned into clothing and jewellery, but it’s fair to say that the one who has integrated repurposing into his creative process throughout his career is undoubtedly the Belgian designer Martin Margiela.

In s/s 1994 he experimented with recreation and recycling, taking older vintage dresses, dyeing, cutting and layering them over a pair of jeans for iconic looks anticipating the still very current trend of layering clothes over jeans or shirts.

Other two fundamental pieces were the a/w 1990 sock jumper where unworn army socks were split, flattened and stitched together to assemble a jumper and the 1999 duvet coats, an excellent repurposing exercise of household objects that paved the road to today’s Balenciaga oversized puffer-coats.

The heir to this creative technique is undoubtedly the contemporary French designer Marine Serre who has the merit of regenerating already existing dormant materials but most of all of being able to scale this process and to bring it again into the catwalks spotlight.

Season after season she has researched and collected multiple deadstock materials such as denim, leather, brocade tapestries, sometimes working with the patchwork technique, other times decorating with the spray technique or using a more contemporary process as laser engraving. She also created entire collections with pre-selected, redyed, disassembled and reassembled t-shirts, silk scarves, jeans or unusual materials such as carpets, brocade tapestries, household linen, cushion covers.

The experimentation carried out by Marine Serre has the material recovery at the core of the design practice and experimentation as framework.

- Transformability by design

To design for transformability is to create a garment or an accessory that can be flexible and adaptive to different styles, occasions and fits.

This is the strongest tool to improve both aesthetical and physical durability because new aesthetics and functions can be created by transformation.

Pioneer is Hussein Chalayan, the Turkish designer at the beginning of the 2000s, created multi-purpose garments with transformation features exploring the boundaries of material and technology in fashion.

Representing the idea of a nomadic existence, in his 00 collection a coffee table transformed into a wooden hooped skirt, models emerged in grey shift dresses and swiped the covers off the chairs and wore them.

In 2007 he showed six mechanised dresses that can be changed into different silhouettes by a machine hidden inside the garment and controlled by a computer system.

Technology was not the only tool that Hussein mastered, in 2013 his dresses transformed again on the catwalks: through the hands of the models, simple cocktail dresses became long evening dresses with a violent tear on the neckline, a wise game of tailoring and expert use of materials.

Today Petit Pli is one of the brands that has moved in the most innovative and transversal way in transformative design.

Founded in 2017 by aeronautical engineer Ryan Mario Yasin, it was inspired by space and deployable satellite technology to design clothing that adapts to children’s rapidly evolving bodies. The company developed a special material that has an auxetic structure through the use of permanent pleating. The pleats move in both directions, either folding together or expanding, so garments can grow up to 7 sizes reducing purchasing costs, extending clothing life and reducing disposal.

The immediate response to the first product launch, led to the idea of ??extending clothing to adults too. A single garment adapts to the body shape and size avoiding premature disposal due to those life changes, such as maternity.

In addition, the clothing collections are made from a 100% recycled polyester Ripstop fabric that is typically woven with a special reinforcing technique that makes material resistant to tearing and ripping, acting on the garment’s physical durability.

- Modularity by design

Modular design is a strategy that separates a product into smaller

parts which can be used or be combined in either the same or a completely different product, giving new life to obsolete unwanted goods. It brings many other advantages as it reduces reliance on virgin raw materials, as well as the energy needed to extract them, simplifying the repair of broken parts.

At the beginning of this century the avant-garde was represented by the Japanese Junya Watanabe. He began his design career as an apprentice patternmaker at COMME des GARÇONS and was greatly influenced by Issey Miyake who deeply studied geometric garment constructions.

In particular, in 2015 Junya explored the field of tessellation, the covering of a surface using one or more geometric shapes repeated. Watanabe focused on the circle form, layering circular modules, intersecting or linking them, introducing contrast of fabrics or colours, using different scales to create irregular patterns or exaggerating sizes to shock proportions.

Yuima Nakazato today is the haute couture designer who continues to develop this concept with the help of the latest innovations.

We cannot summarise his prolific activity of research, but it’s interesting mentioning his 3D unit constructed textile, made using digital fabrication. This simple system combines two types of units (modules) that can adjust the size and shape of a garment to have the precise fit without the use of traditional sewing patterns.

- Repair/Mending

Repairing and mending are strategies mainly related to the post-sell phase, hence up to consumer will and skills.

However, product’s repairability is determined at the design phase therefore design decisions from material selection to how the product is assembled, will all impact how likely a product is to be repaired rather than replaced. Durable, commercially available materials and detachable accessories aid future repairs.

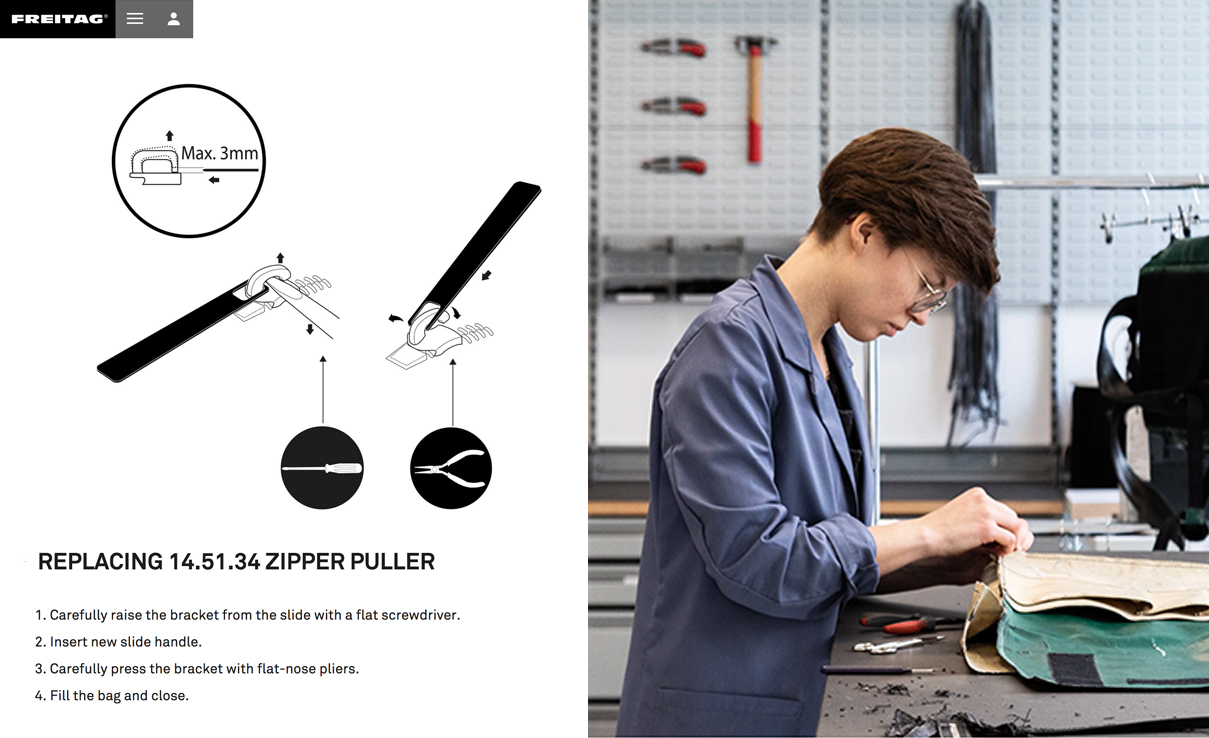

In Europe, almost everyone knows Freitag bags from brothers Daniel and Markus Freitag who have been designing durable, functional and water-repellent bags since 1999 using old truck tarps, discarded bicycle inner tubes and car seat belts. The brand is not only a cornerstone of recycling by design in the world of clothing, but also supports customers with a repair service that goes beyond the remote corporate repair service by incorporating a repair station in most of their flagship stores.

However, what truly sets their approach apart is providing users with replacement parts such as screws, straps, rubber parts, and studs that can be replaced by themselves or through a local shoemaker.

For a few years now many people have become passionate about repairs with an increasingly creative DIY approach, gathering in communities that share skills and tutorials on the web.

There are many names that do this under the global trend named “visible mending” such as the Scottish Flora Collingwood who champions this art as part of her waste reduction philosophy; her mendings are very precise, flat and geometric and have become the inspiration for a real pattern in her standard knitwear collection.

An example in a more mainstream context is Coach’s spring 2023 collection in which some designs featured visible mending with coloured thread, an evolution of a hand work into an artistic craft, emphasising both sustainability and a distinctive aesthetic.

In accessories as well, the Spanish fashion house Loewe has commissioned artisans from Galicia to restore and reimagine antique woven baskets from around the world, using leather, and inspired by the idea of ??Japanese kintsugi, which amplifies the beauty ennobling the repair itself.

It is precisely this ennoblement that is the most interesting feature of this phenomenon where mending has become visible, declared, displayed with pride so much as to become a decoration, an aesthetic, “to proudly wear the (inevitable) change towards a circular future of the fashion industry”.

Sources

- Fashionunited.com

- Onlife fashion, P.Kothler, Hoepli 2021

- BoF report “Gen Z and fashion in the age of realism”, 2022

by OpenDot and Linda Zamboni, teacher in Sustainable Fashion at Istituto Marangoni